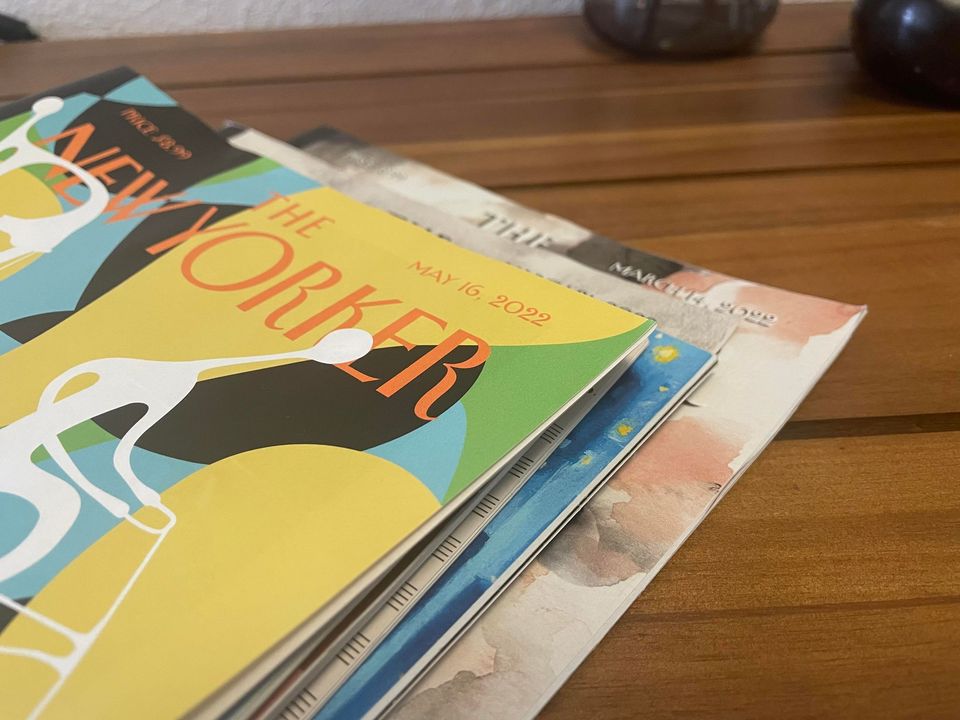

The New Yorker Stack

On my dining table sits a stack of print editions of the New Yorker. The cover designs of the March 14th and March 21st editions protrude slightly from the base, its revealing edges of the depicted war across the globe. At the top of the stack is the May 16th edition, a vibrant and abstract piece of four humanoid figures cycling. As I write this, on May 21st (a full two months since my last post, sorry), this week’s edition certainly awaits in the mail along with coupons and envelopes addressed to the previous tenant. By next week, the May 23rd edition will hold the top position, the May 30th edition will await in the dark, and the war will be piled with more unread articles and abstract art.

When I glance at the New Yorker pile it is an unsettling reminder of privilege. Mimicking the public attention span, the war in Ukraine was artistically highlighted for a few weeks and then quickly displaced. For those unaffected, the global conflict is a blip in our worldly perceptions. A new topic of discussion, a source of pain and outrage, a community to extend prayers and financial assistance. For the affected, the war, with all its fear and uncertainty, was everything. For us, the privileged, it was something…until it just wasn’t. In time, the privileged become desensitized to the conflict and share compassion diminishingly, until the next tragedy. No longer Ukraine, but abortion rights, and then, no longer abortion rights, but gun control. Within the subtext of reform and justice is a cycle of compassion, then negligence.

This is not to say that media reporting is dishonest or heartless, or that one conflict deserves more focus than the others. I mention this because while the privileged can empathize and support the affected, compassion always seems to be a finite resource. We, the privileged, consume news and media to empathize with loss, but always with the security to plug our ears and shut out eyes.

The same cannot be said for those that truly experience loss and pain. They plug their ears and still hear cries. They shut their eyes and still see catastrophe. And months after the media and public spotlight shifts, the pain of loss still etches deeper wounds—this is the tragedy after the tragedy.

So when I look at the stack of New Yorker magazines, I’m reminded of my own unfair and irrational privilege. The stack contains dozens of articles written by bright minds, each of which exist for my consumption. Despite my being unencumbered by literacy and time, the stack remains largely unread. And it’s not just the stack, of course, that screams privilege. It’s in the dining table where the stack sits. It’s in the adjacent refrigerator and stocked pantry. It’s in all my things, but more jarringly, it’s in all my thoughts too.

Like the itinerant media landscape, I’m privileged to express, then move on. I’m privileged to be infuriated with political discourse one week and distressed about the climate the next. Like public compassion, my fervor climbs, peaks, then steadily declines, only to climb again for the next issue. This cycle has often led to helplessness- the feeling that each of the countless issues seem too large and too looming to resolve.

In a world, with seemingly endless problems and tragedies, there’s even a subtle hint of privilege to worldly despair. Relatively unbothered by catastrophes such as war or personal loss, we, the privileged, are able to latch onto all issues and express concern everywhere. Similar to the paradox of choice, with minor dilemmas to endure, we overwhelm ourselves with despair. But what is the correct response to this despair? Is it fervor or is it indifference?

Hank and John Green, name this feeling of universal despair as “The Sad Gap”. In a video, John Green discusses traversing the Sad Gap—defeating the feeling of despair and hopelessness. Our Sad Gaps are born out of our privilege to freely empathize over tragedies and our inability to solve them. Overwhelmed with hopelessness, we are immobilized with despair and stray towards inaction.

However, John suggests a solution- finding a priority. In the video, he says, “a lot of philanthropy was about us-our feeling of helplessness, our desire to do something”, when rather, it should be about the communities we wish to serve. In all my privileged selfishness, I often ask, what can I do, for every new rising issue.

John unknowingly answers this question by saying, find a priority. That is, find something you care about, and stick to it. Our ability to express compassion over everything will falter, but over one thing, it will thrive. To traverse the Sad Gap, John focuses his philanthropy on improving maternal and child health in West Africa and his brother addresses the climate crisis. That is not to say they care little about conflicts overseas or women’s rights—they do, they simply have chosen a primary focus. By going deep on their priorities and educating those around them, their impact multiplies, and their priorities see growth.

Having a priority also remedies the privileged cycle. Rather than slicing our compassion, a priority helps us still empathize with the world but direct our compassion deliberately.

To be privileged means we have the liberty to plug our ears and shut our eyes. To be affected means they cannot. For one community, just one, we should strive to not divert our attention, but listen and watch with compassion, and make them our priority.

Thanks for reading! If you liked it, please share it with a friend! If you didn't, I'm sorry. :(

Email me (openthoughtblog@gmail.com) and let me know how I did or if you have any critiques, comments, or recommendations. If you liked this or any other post, please consider subscribing. :)

Member discussion